We come now to Tom-All-Alone’s, a London slum.

Please stay close by me! I would hate for us to be separated. I hesitated to take you here, but then I reminded myself: “Esther! sometimes it is best to face a problem squarely.”

Introducing Tom-All-Alone’s.

Ours is a journey of contrasts, and indeed Mr Dickens’s England is an England of contrasts.

Dickens’s reformist social vision was widely noted by his contemporaries, the Edinburgh Review, for example, observing that he “directs our attention to the helpless victims of untoward circumstances, or a vicious system—to the imprisoned debtor—the orphan pauper—the parish apprentice—the juvenile criminal—and to the tyranny, which, under the combination of parental neglect, with the mercenary brutality of a pedagogue, may be exercised with impunity in schools.” Catherine Waters, “Reforming Culture,” in John Bowen & Robert L. Patten, Eds., Charles Dickens Studies. London: Palgrave Advances, 2006, 155-176; 158.

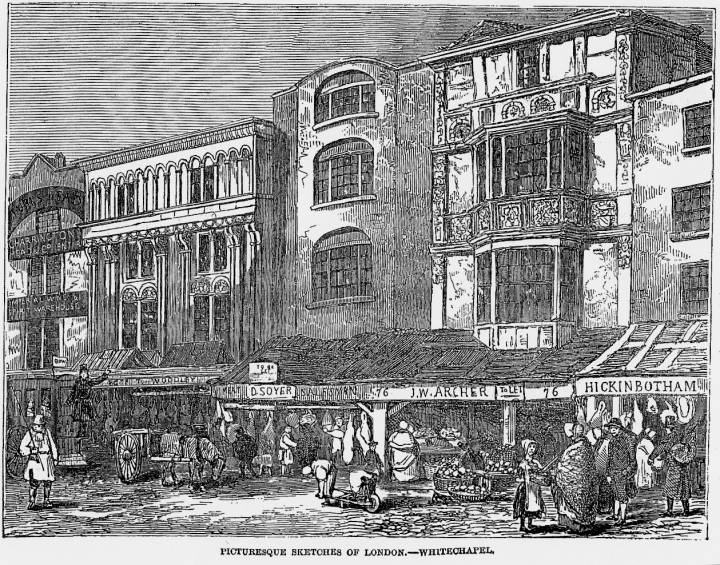

Tom-All-Alone’s, a London slum, is within walking distance of the bureaucratic muddle, whirl, and inaction of Chancery. It is in the City of London! It is a disgrace that within sight of the wealth of the city lurks such misery and poverty, and indeed Bleak House is only one of Mr Dickens’s novels that discusses the misery of the slums. Tom-All-Alone’s functions in Bleak House as a reminder that we are all responsible for the well-being of our fellow humans, and that even those of us at the very pinnacle of society cannot entirely divorce ourselves from what lies below.

Location

Tom-All-Alone’s is located, as I say, only walking distance from Chancery, from the bustle and dash of the Inns of Court, and the main thoroughfares of London. If you are familiar with social maps, such as Poole’s map of London poverty, you will know that for most of London’s history, poor areas, slums or worse, exist not so far from wealth.

Darkness rests upon Tom-All-Alone's. Dilating and dilating since the sun went down last night, it has gradually swelled until it fills every void in the place. For a time there were some dungeon lights burning, as the lamp of life hums in Tom-all-Alone's, heavily, heavily, in the nauseous air, and winking—as that lamp, too, winks in Tom-all-Alone's—at many horrible things. But they are blotted out. The moon has eyed Tom with a dull cold stare, as admitting some puny emulation of herself in his desert region unfit for life and blasted by volcanic fires; but she has passed on and is gone. The blackest nightmare in the infernal stables grazes on Tom-all-Alone's, and Tom is fast asleep.<br /> Much mighty speech-making there has been, both in and out of Parliament, concerning Tom, and much wrathful disputation how Tom shall be got right. Whether he shall be put into the main road by constables, or by beadles, or by bell-ringing, or by force of figures, or by correct principles of taste, or by high church, or by low church, or by no church; whether he shall be set to splitting trusses of polemical straws with the crooked knife of his mind or whether he shall be put to stone-breaking instead. In the midst of which dust and noise there is but one thing perfectly clear, to wit, that Tom only may and can, or shall and will, be reclaimed according to somebody's theory but nobody's practice. And in the hopeful meantime, Tom goes to perdition head foremost in his old determined spirit.<br /> But he has his revenge. Even the winds are his messengers, and they serve him in these hours of darkness. There is not a drop of Tom's corrupted blood but propagates infection and contagion somewhere. It shall pollute, this very night, the choice stream (in which chemists on analysis would find the genuine nobility) of a Norman house, and his Grace shall not be able to say nay to the infamous alliance. There is not an atom of Tom's slime, not a cubic inch of any pestilential gas in which he lives, not one obscenity or degradation about him, not an ignorance, not a wickedness, not a brutality of his committing, but shall work its retribution through every order of society up to the proudest of the proud and to the highest of the high. Verily, what with tainting, plundering, and spoiling, Tom has his revenge.<br /> It is a moot point whether Tom-all-Alone's be uglier by day or by night, but on the argument that the more that is seen of it the more shocking it must be, and that no part of it left to the imagination is at all likely to be made so bad as the reality, day carries it. The day begins to break now; and in truth it might be better for the national glory even that the sun should sometimes set upon the British dominions than that it should ever rise upon so vile a wonder as Tom. (Bleak House, Chapter XLVI ‘Stop Him!’)

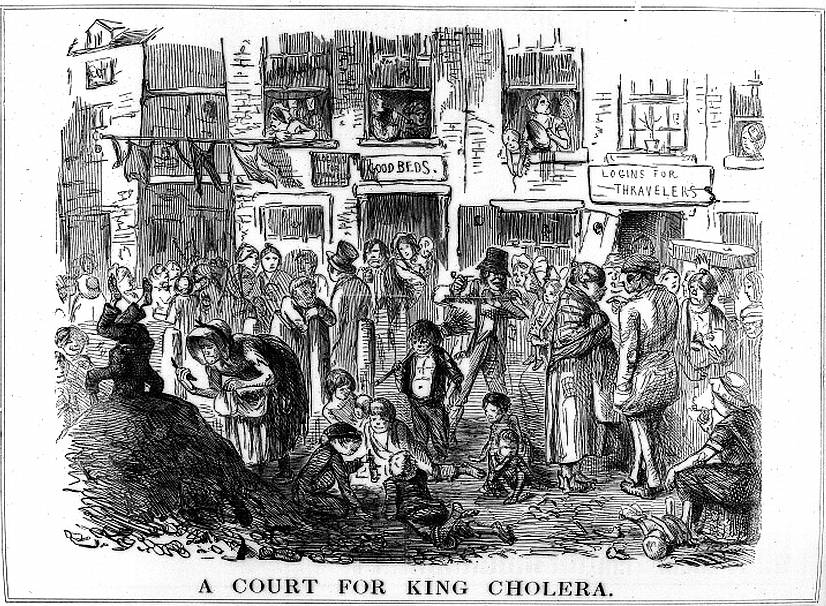

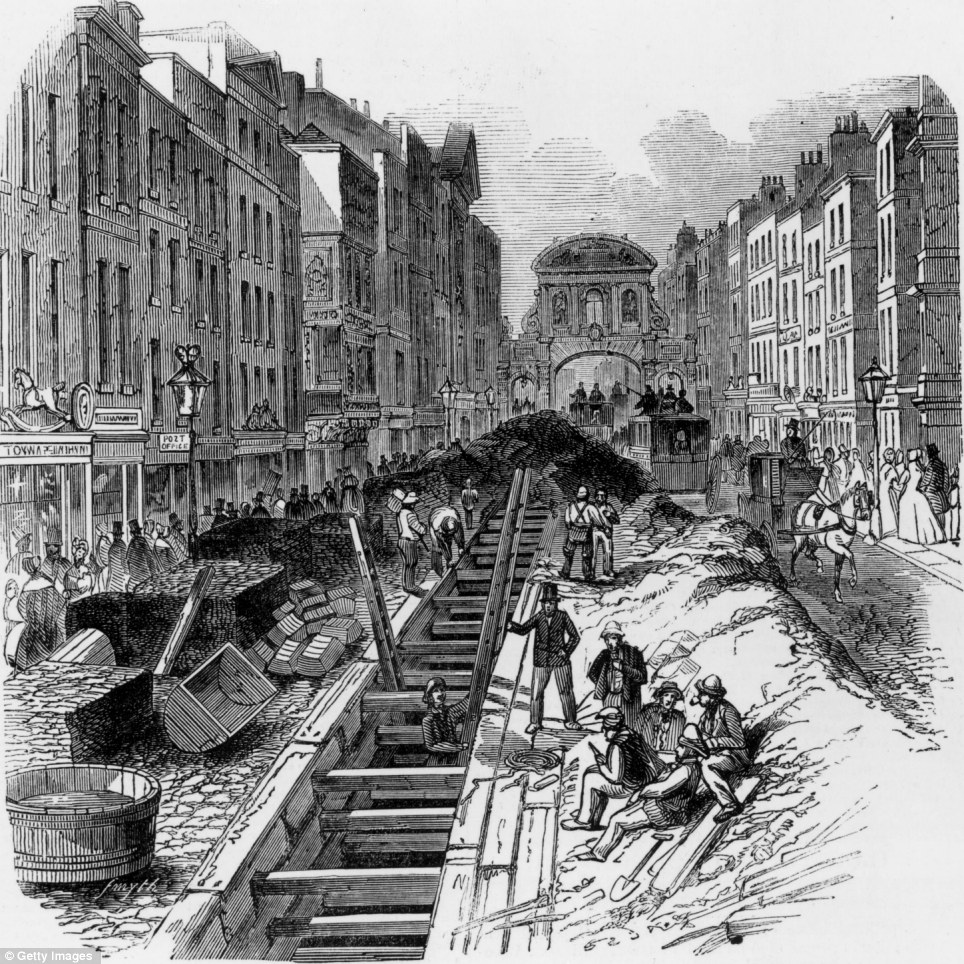

Much of this has to do with high areas and low areas, whereby high areas are easier to build on, and better sanitized, while lower areas are damper, and more difficult to build on. As Bleak House is being written, sanitation crises rage, and the overhaul of London’s sewage system is being embarked upon. Tom-All-Alone’s is an example of a slum area, fallen into disrepair by virtue of its less salubrious location, and by the neglect of its landlords. Though it is out of sight, and out of mind, for most Londoners, who avoid walking through it, or pass by unawares down the main, and safer, streets, it is centrally located in the City.

Purpose and Nature in the world.

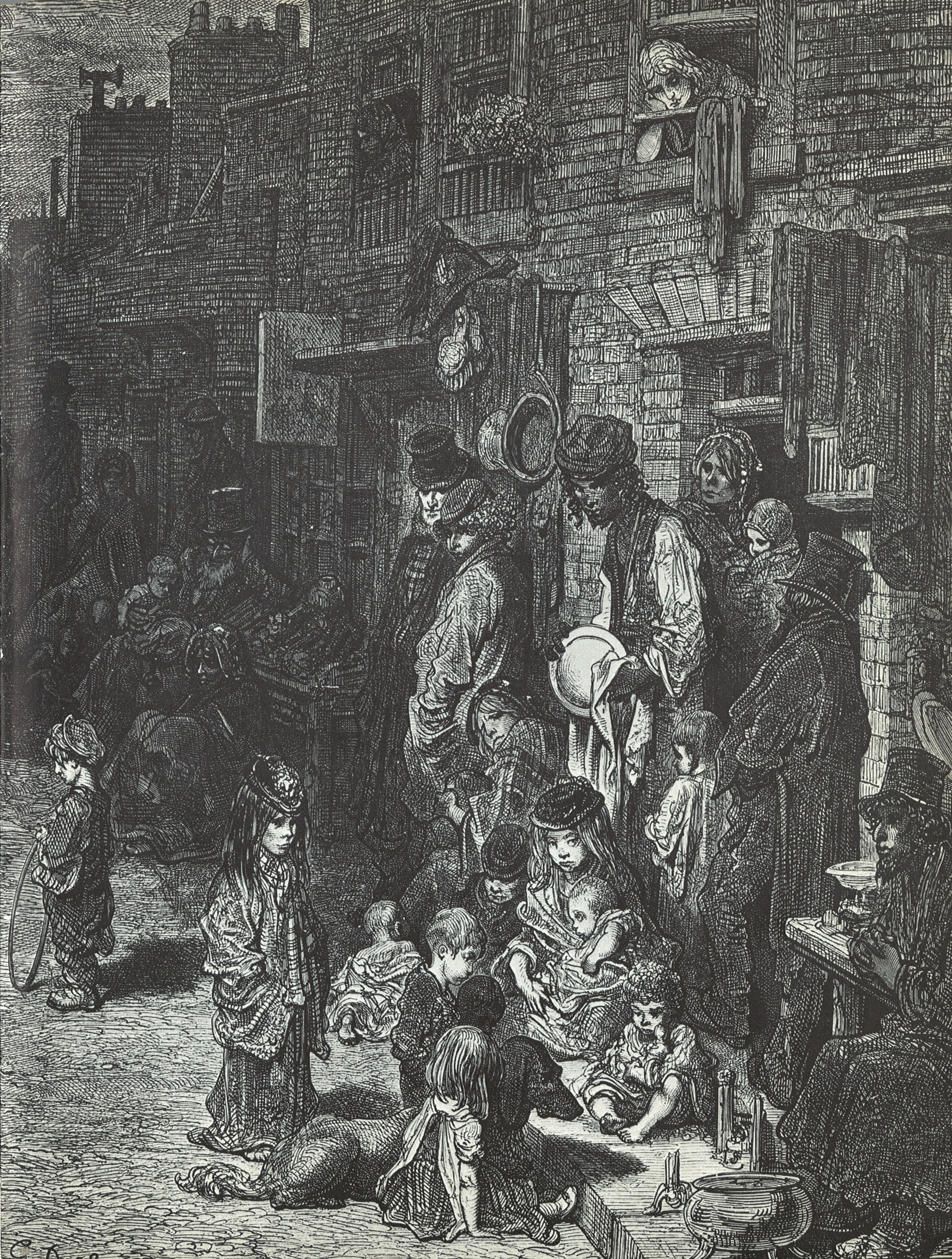

The people who live in slums do so because they have nowhere else to go. As Mr Dickens describes, they pile in, almost one on top of the other, each capturing their own little corner, coexisting in a rough-and-ready, almost animal fashion, that greatly contrasts with the codes of behaviour, and rules of family and property ownership in wealthier parts. Slums exist because poverty exists, and poverty is a great leveller. Poverty exists because there is little work for the labouring classes; there is little education to enable the poor to rise in the world. Great social shifts have occurred in England, meaning that the people from the countryside who come to London to seek their fortune, are unlikely to find what they seek. The most unfortunate of these come to places like Tom-All-Alone’s.

Mr Dickens names the place Tom-All-Alone’s after a boyhood memory of a house built by a local eccentric. Its name sums up the invidual and collective misery and loneliness of the place. Ironically, it is a place that is subject to Chancery, being one of the named possessions in dispute in the Jarndyce vs. Jarndyce legal suit. My guardian, Mr Jarndyce, that kindest of men, is the landlord, unable to pursue any means to clean it up. And so it rots, in view of the wealthiest parts of London, a reminder of the misery that wealth ignores .

Description.

Who better to describe Tom-All-Alone’s than Mr Dickens. As you know, he narrates part of Bleak House, while I do my best with my part. Here is how he describes it when we first come to it.

It is a black, dilapidated street, avoided by all decent people, where the crazy houses were seized upon, when their decay was far advanced, by some bold vagrants who after establishing their own possession took to letting them out in lodgings. Now, these tumbling tenements contain, by night, a swarm of misery. As on the ruined human wretch vermin parasites appear, so these ruined shelters have bred a crowd of foul existence that crawls in and out of gaps in walls and boards; and coils itself to sleep, in maggot numbers, where the rain drips in; and comes and goes, fetching and carrying fever and sowing more evil in its every footprint than ... all the fine gentlemen in office, . . . shall set right in five hundred years—though born expressly to do it. (Bleak House, Chapter XII, 'Tom-All-Alone's.')

Its darkness, dirtiness, squalor tell us as much as we need to know about this terrible place. And it is a place that infects those it touches, as we see in a later description, in which Mr Dickens describes Tom-All-Alone’s ‘revenge’ upon all strata of society. Like the fog that covers, and adds to, the dirt and confusion of London, like the busy stasis of Chancery that infects all it touches, Tom-All-Alone’s is always with us. It is everywhere and nowhere; we can ignore it, but we cannot escape its touch.

Function in Bleak House

As I say, ours is a journey of contrasts, and Tom-All-Alone’s provides a dramatic contrast with the bureaucratic muddle of Chancery, and later with the chilly wealth of Sir Leicester and Lady Dedlock, and the warmth and cheeriness of Bleak House itself.

It is precisely the dynamic tension between social awareness and imaginative excess that creates the special ambience of his novels. Elana Gomel. “Part of the Dreadful Thing”: The Urban Chronotope of Bleak House. Partial Answers 9/2: 297-309, 2011., 297-309, 298.

Its central location reminds us of how close by poverty exists to wealth, and makes the point that the wealthy ignore the poor at their peril. Its filth and disease (the smallpox that kills Jo, and disfigures me) emanate outwards, not unlike the fog of London. Like Chancery, and like the fog, Tom-All-Alone’s is symbolic to some degree. It is symbolic of misery, darkness, crime, and neglect. When characters like Lady Dedlock visit, for the purpose of uncovering the whereabouts of Nemo (Captain Hawdon, my father), it is a reminder that even the greatest of us may have things in our past we wish to hide.

When Jo the crossing sweeper, a boy who plays an important role in this novel, enters it and exits it, his broom (his livelihood) in his hands, it is both a refuge and a curse to him: a refuge, because he has nowhere else to rest (being forever elsewhere told to move on), but a curse because of its filth, squalor and dangerousness.

Normally, ordinary people like myself would avoid it at all costs, for fear of being set upon by thieves or worse. In writing about Tom-All-Alone’s, Mr Dickens (who is famous for his depictions of the disgrace of Victorian poverty), reveals to us, and reminds us, of the heart of darkness in our city.

Come! Perhaps it is time we moved on, ourselves.