Social Problems. Poverty, Illness and Sanitation Reform.

“The Poor you will always have with you,” says the Book of Matthew. And indeed Bleak House is peopled with those who live in the misery of poverty, suffering at first hand the unfortunate effects of unsanitary conditions in London and abroad.

General Introduction.

Social problems, such as poverty, illness, and sanitation reform, are dominant themes of this novel, seen mainly in the depiction of Poor Jo, and of Jenny, the Brickmaker’s wife. Mr Dickens’s sympathies, as I believe I have said elsewhere, are with the poor, who suffer most from the unsanitary conditions of the city, being unable to escape it. Mr Dickens felt very strongly the misery of the poor. He himself had a troublesome brush with poverty in his childhood, and he never forgot it. In Bleak House, he directs his anger at the systems that neglect the poor, and keep them in their miserable place. In his depiction of the poor and the things they suffer, he is sympathetic, some might even say sentimental, doing so in order to arouse our own sympathies and anger, with the hope of making some changes.

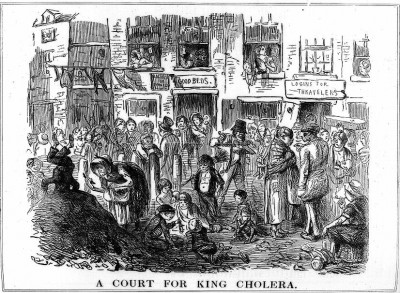

Edwin Chadwick had identified the miasma emanating from defective sewerage and drainage in overcrowded poor districts as a key cause of disease in his monumental Report on the Sanitary Condition of the Labouring Classes of Britain (1842), where the need for centralized administration of public health is advocated inorder to oversee not only the construction of public utilities like sewers but the regulation of the homes and habits of the poor, especially the Irish. Dickens was a zealous supporter of the sanitary reforms proposed in the 1840s by Chadwick. Catherine Waters, ‘Reforming Culture,’ in Palgrave Advances in Charles Dickens Studies. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006. 155-174; 164

Poverty.

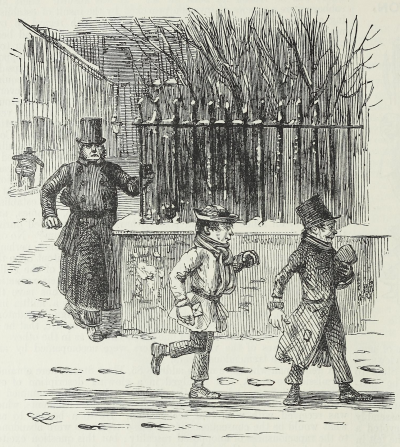

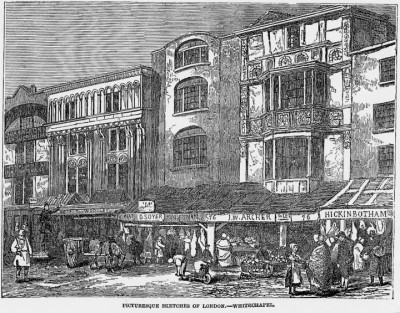

You may remember our visit to Tom-All-Alone’s, where poor Jo lives with other unfortunate souls.

Jo lives—that is to say, Jo has not yet died—in a ruinous place known to the like of him by the name of Tom-all-Alone's. It is a black, dilapidated street, avoided by all decent people, where the crazy houses were seized upon, when their decay was far advanced, by some bold vagrants who after establishing their own possession took to letting them out in lodgings. Now, these tumbling tenements contain, by night, a swarm of misery. As on the ruined human wretch vermin parasites appear, so these ruined shelters have bred a crowd of foul existence that crawls in and out of gaps in walls and boards; and coils itself to sleep, in maggot numbers, where the rain drips in; and comes and goes, fetching and carrying fever and sowing more evil in its every footprint than Lord Coodle, and Sir Thomas Doodle, and the Duke of Foodle, and all the fine gentlemen in office, down to Zoodle, shall set right in five hundred years—though born expressly to do it. (Bleak House, Chapter XVI, ‘Tom-All-Alone’s.’)

This derelict slum is fallen into disrepair as it is contested property under the Jarndyce v. Jarndyce lawsuit. In the heart of London, walking distance from some of the wealthiest parts of the city, how can people be living like this!

When they come at last to Tom-all-Alone's, Mr. Bucket stops for a moment at the corner and takes a lighted bull's-eye from the constable on duty there, who then accompanies him with his own particular bull's-eye at his waist. Between his two conductors, Mr. Snagsby passes along the middle of a villainous street, undrained, unventilated, deep in black mud and corrupt water—though the roads are dry elsewhere—and reeking with such smells and sights that he, who has lived in London all his life, can scarce believe his senses. Branching from this street and its heaps of ruins are other streets and courts so infamous that Mr. Snagsby sickens in body and mind and feels as if he were going every moment deeper down into the infernal gulf. (Bleak House, Chapter XXII, ‘Mr Bucket.’)

Illness.

Illness is with us all. Poor Jo carries the illness and degradation of Tom-All-Alone’s to Bleak House, and infects both Charley Neckett and myself with smallpox. Though we all recover, Jo later dies from pneumonia. His young frame is weakened by poverty and by his illness.

Illness can make its way through every level of society, though it affects the poor first, and in the greatest numbers.

Mr Dickens’s grasp on theory of germs and infections is a little limited (as indeed my dear husband, Mr Woodcourt, might say). He ascribes to the Miasmic theory, whereby germs are transferred through vapours, fumes, and fog. In fact, as you doubtless know, they are more likely transferred through touch. Mr John Snow discovered this not long after Bleak House was written, when he connected the cholera epidemic sweeping London with the handle of a local water pump, near Broad Street.

Sanitation Reform.

As the sickening description of the pestilential graveyard where Nemo lies buried in Bleak House would suggest, the problems of pollution and disease caused by intramural interment were of particular concernto Dickens, and Household Words carried a number of articles throughout the 1850s in support of the Board of Health and its efforts to reform burial practices. Catherine Waters, ‘Reforming Culture,’ in Palgrave Advances in Charles Dickens Studies. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006. 155-174; 164-5

While illness functions as a theme that sweeps through all layers of society, Mr Dickens is nevertheless also practical. He advocates sanitation reform.

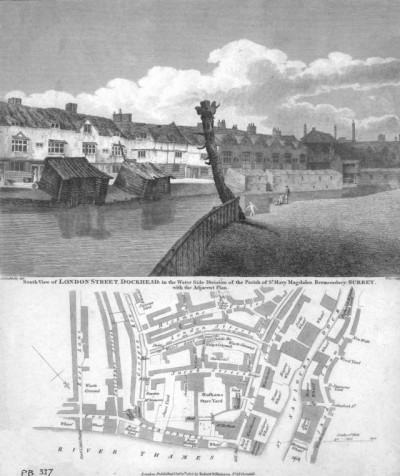

The great city of London is expanding exponentially, and it lacks what you would call infrastructure—systems of transport and methods of dealing with waste being the most noticeable.

As Mr Dickens writes, sanitation reform is under way. The installation of great sewage systems had a remarkable and positive effect on life and conditions in London!