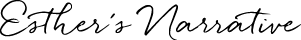

It is time to enter into specific places, to clear the fog away. We therefore start, where the fog is thickest, at the Courts of Chancery.

Introducing Chancery.

Mr Dickens uses the term ‘Chancery’ to refer to the political and legal systems that are at the heart of Britain’s governing processes. Chancery is located in the heart of the City of London. It includes the Courts, where lawsuits grind their way slowly through bureaucratic motions and remotions. It is where the lawsuit that affects us all, in Bleak House, is slowly withering the lives of those who are caught up in it. It functions in this novel as a symbol of ‘stasis,’ whereby no improvements in individual or general cases can be made, causing considerable grief to us all.

The raw afternoon is rawest, and the dense fog is densest, and the muddy streets are muddiest near that leaden-headed old obstruction, appropriate ornament for the threshold of a leaden-headed old corporation, Temple Bar. And hard by Temple Bar, in Lincoln's Inn Hall, at the very heart of the fog, sits the Lord High Chancellor in his High Court of Chancery. Never can there come fog too thick, never can there come mud and mire too deep, to assort with the groping and floundering condition which this High Court of Chancery, most pestilent of hoary sinners, holds this day in the sight of heaven and earth. (Bleak House, Chapter I, ‘In Chancery’)

Location

As one of the key places amongst which the novel is set, it seems appropriate that Chancery is centrally located in the City of London. Mr Dickens suggests that the fog is thickest here, because of the stasis, inaction, and inability to do what is best for the country. He may, of course, be speaking somewhat emotionally, or indeed, indulging in a touch of literary symbolism. On that matter, I will leave you to be the judge!

The Courts of Chancery are located close to the borough of Holborn, where much of the London action takes place.[1] Around them are busy streets, full of houses, shops, and places of work. Major roads, such as Chancery Lane, pass them by, connecting them with the rest of London.

Purpose and Nature in World

For many years, the Courts of Chancery were a major part of British legal life. (Indeed, dare I say, they were a major part of the difficulties of British legal life!) Chancery is a place of lawsuits and of bureaucracy, a place where petitioners can wait years for resolution. Some lawsuits, such as the Jennings lawsuit, were in court for several decades, and the entire estate consumed in legal costs![2]

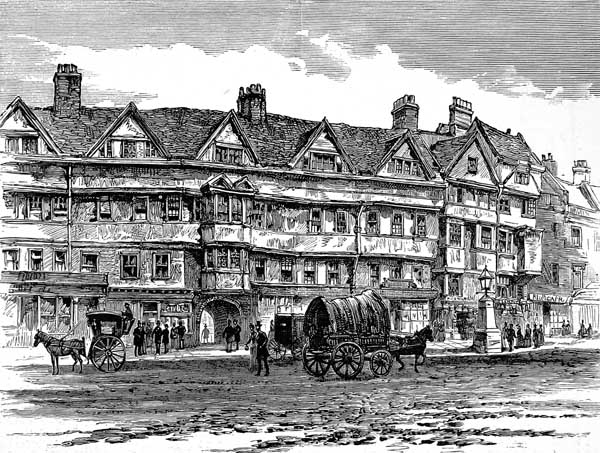

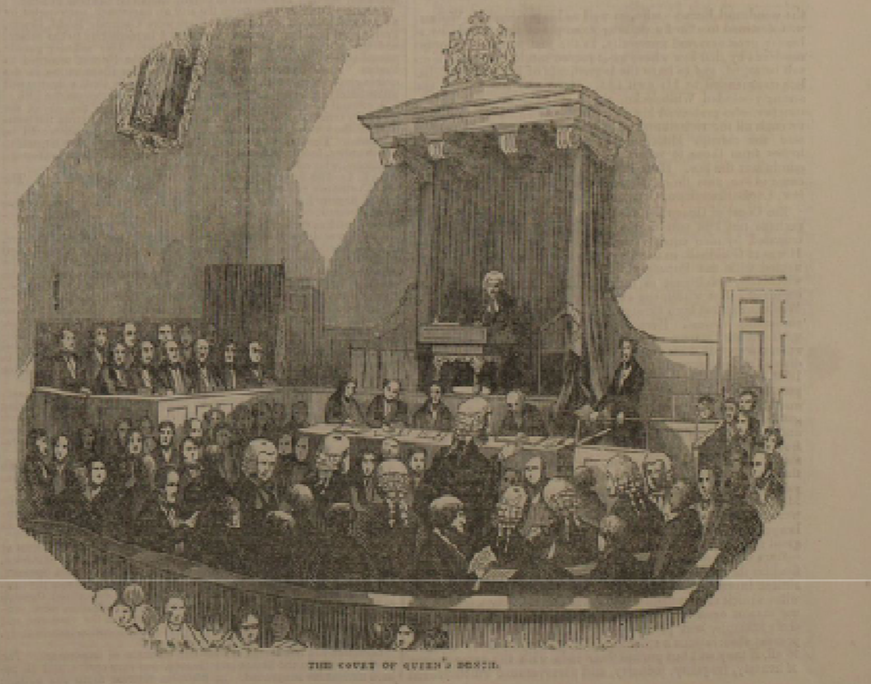

The Courts of Chancery are where the legal disputes take place in front of the judge.

On such an afternoon, if ever, the Lord High Chancellor ought to be sitting here - as here he is - with a foggy glory round his head, softly fenced in with crimson cloth and curtains, addressed by a large advocate with great whiskers, a little voice, and an interminable brief, and outwardly directing his contemplation to the lantern in the roof, where he can see nothing but fog. On such an afternoon some score of members of the High Court of Chancery bar ought to be -as here they are -mistily engaged in one of the ten thousand stages of an endless cause, tripping one another up on slippery precedents, groping knee-deep in technicalities, running their goat-hair and horsehair warded heads against walls of words and making a pretence of equity with serious faces, as players might. On such an afternoon the various solicitors in the cause, some two or three of whom have inherited it from their fathers, who made a fortune by it, ought to be—as are they not? - ranged in a line, in a long matted well (but you might look in vain for truth at the bottom of it) between the registrar's red table and the silk gowns, with bills, cross-bills, answers, rejoinders, injunctions, affidavits, issues, references to masters, masters' reports, mountains of costly nonsense, piled before them. Well may the court be dim, with wasting candles here and there; well may the fog hang heavy in it, as if it would never get out; well may the stained-glass windows lose their colour and admit no light of day into the place; well may the uninitiated from the streets, who peep in through the glass panes in the door, be deterred from entrance by its owlish aspect and by the drawl, languidly echoing to the roof from the padded dais where the Lord High Chancellor looks into the lantern that has no light in it and where the attendant wigs are all stuck in a fog-bank! This is the Court of Chancery, which has its decaying houses and its blighted lands in every shire, which has its worn-out lunatic in every madhouse and its dead in every churchyard, which has its ruined suitor with his slipshod heels and threadbare dress borrowing and begging through the round of every man's acquaintance, which gives to monied might the means abundantly of wearying out the right, which . . exhausts finances, patience, courage, hope, so overthrows the brain and breaks the heart (Bleak House, Chapter I, ‘In Chancery’)

Mr Dickens also uses the term Chancery to refer to more than merely the courts. He refers to the legal profession that pursues the case. Near the Courts are the Inns of Courts, which are a group of bodies overseeing the lawyers. Barristers in England must connect to the Inns. Law students, trainee lawyers, established lawyers, and law firms are all connected to these Inns. (Mr Dickens himself, for a time, trained in the law at Lincoln’s Inn.) Ironically, while the legal petitioners’ money is consumed by the business of the court, a great number of professions thrive on the work. Judges, lawyers, clerks, copyists, stationers, detectives, all carry out their business at the expense of the litigants. Some are good people, some are not so good, and at times, Mr Dickens refers to them all as ‘Chancery.’ You see how the fog pervades the city—literally, and figuratively, through the roles and actions of the many players in the endless roundabout of legal action and inaction!

Description in the Novel

Chancery itself is an old building, purpose-built, for the hearing of cases. Mr Dickens describes it thus.[4] It is a place, then, but it is the people in the place who create the fog! And it is an important place in the novel because its actions (or inactions) affect important people in Bleak House. It therefore does not merely function as a symbol of bureaucracy and inaction. Key players in the novel are connected through Chancery, through a tangled lawsuit, in which litigants dispute their right to funds from a missing will, signed by Mr Thomas Jarndyce. This legal dispute, known as Jarndyce vs. Jarndyce, has been crawling through the courts (through Chancery) for decades. Mr John Jarndyce, is connected with the case, as are his wards, Richard Carstone and Ada Clare, young cousins, for whom I am engaged as a companion.

As they wait fruitlessly for a settlement of some kind, Richard vacillates between careers, spending money against his expectations, and falling in love with Ada. Mr John Jarndyce is a kind and genial man, related to the original disputants. He is distressed by the years and lives wasted in lawsuits that have ground through the courts.

To point out the degree of wastage and tragedy associated with Chancery, Mr Dickens draws our attention to a number of businesses connected to it, and acting similarly. We might call these ‘in the shadow of Chancery.’

Near to Chancery is a bustling street called Chancery Lane. Just off Chancery Lane is Cursitor Street, where a Stationer, Mr Snagsby, presides over another set of Chancery-related matters—namely the professional documenting and organizing required in the background. The lawyers and barristers argue and counter argue, and evidence is submitted and resubmitted. It is all done on paper, and copied by copyists, and clerks: Mr Snagsby passes this work on to them. Mr Snagsby is a good man, but worried by the endless flow of paper and information and the ruined lives around him.

A not so good man is Mr Vholes, a lawyer and money lender who preys on the weakness of my dear Richard, encouraging him to borrow against his expectations, until Richard is sunk, financially. His office is like a lair, in which a predator lurks, waiting for the unwary to stumble by, and he preys on poor Richard, until his money and expectations have wasted away to nothing. I am not fond of Mr Vholes!

One further example, though I dislike taking you here, because of the so many tragic incidents that have occurred here, is Krook’s Rag and Bottle Warehouse.

Krook’s Rag and Bottle Warehouse is a mirror image, in small form, of the wastage and foolishness emanating from the courts of Chancery. It is a place where waste comes, to be sold again for re-use, or to accumulate in corners that no one looks at. Mr Krook, the proprietor, whom you see in the image above, is a nearly illiterate old man, who presides over the accumulation of wastage. It is he who holds the key to the ongoing chaos of the Jarndyce vs Jarndyce case, in the form of missing documents, but his illiteracy and insanity prevent him from recognising or sharing that information. He meets a tragic end, when he spontaneously combusts (it is a strange thing to happen!), and others find the documents in the end. But it is no coincidence that Mr Dickens calls him ‘The Lord Chancellor,’ for his warehouse functions much like the courts, as a repository of useless information, where valuable things are hidden or wasted.

Function of Chancery

Through his depiction of Chancery, and its role in the plot of Bleak House (bringing myself together with Richard, Ada, and Mr Jarndyce, but also with Mr Krook, Nemo (Captain Hawdon, my father), and many other characters, Mr Dickens satirizes what he perceives as a broken political and legal system. He does so with the power of his pen, showing us, through Chancery, and the shadow chanceries I have mentioned, the tragedy of a whole society caught up in its workings.

Around and around the court of Chancery, then, we see the life of London swirling—the poor petitioners in the law suits, the lawyers and their chambers, the clerks and copyists, and the rubbish and flotsam that associates loosely with them. Perhaps most starkly we see the tragedies of the stasis of Chancery laid bare in the lives of those associated with Mr Krook, but we cannot separate ourselves so easily from that tragedy, entwined as we all are to our different degrees in the case. Little wonder that Mr Dickens says that the fog lies thickest over this place–it is a veritable hive of fruitless and wasteful activity, purposeful only in creating work for itself.

The one great principle of the English law is to make business for itself. There is no other principle distinctly, certainly, and consistently maintained through all its narrow turnings. Viewed by this light it becomes a coherent scheme and not the monstrous maze the laity are apt to think it. Let them but once clearly perceive that its grand principle is to make business for itself at their expense, and surely they will cease to grumble. (Chapter XXXIX, ‘Attorney and Client.’)

Mr Dickens says, in reference to Mr Vholes, but it can equally be applied to Chancery, that the ‘one great principle of the English law is to make business for itself. There is no other principle distinctly, certainly, and consistently maintained through all its narrow turnings. Viewed by this light it becomes a coherent scheme and not the monstrous maze the laity are apt to think it. Let them but once clearly perceive that its grand principle is to make business for itself at their expense, and surely they will cease to grumble.’

This is not a cheering thought!