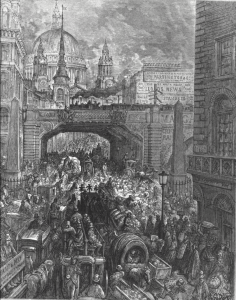

We begin, where Bleak House begins, in the heart of London.

Introducing London.

London, the heart of the nation, is the heart of Bleak House, in geographical and emotional terms. Mr Dickens opens Bleak House with a description of London, that sets the scene for our understanding of the novel, as showing the condition of England, and showing that it is wanting.

London. Michaelmas term lately over, and the Lord Chancellor sitting in Lincoln's Inn Hall. Implacable November weather. As much mud in the streets as if the waters had but newly retired from the face of the earth, and it would not be wonderful to meet a Megalosaurus, forty feet long or so, waddling like an elephantine lizard up Holborn Hill. Smoke lowering down from chimney-pots, making a soft black drizzle, with flakes of soot in it as big as full-grown snowflakes—gone into mourning, one might imagine, for the death of the sun. Dogs, undistinguishable in mire. Horses, scarcely better; splashed to their very blinkers. Foot passengers, jostling one another's umbrellas in a general infection of ill temper, and losing their foot-hold at street-corners, where tens of thousands of other foot passengers have been slipping and sliding since the day broke (if this day ever broke), adding new deposits to the crust upon crust of mud, sticking at those points tenaciously to the pavement, and accumulating at compound interest. (Chapter One: In Chancery)

Location in England.

London is the capital of England, and is located at the mouth of the Thames River, in the South East of the country. At the time of Bleak House, it contains over two million people (2,350,000 in 1851), and covers many miles. At its heart is the City of London: one square mile of buildings and streets, great and small, full of people, buildings, streets, objects, animals—full of life!

Purpose and Nature.

As the capital city, London is the heart of the nation’s political and legal system, to say nothing of its business and cultural matters. Parliament sits in London. The Queen has her primary residence in London. The Law Courts do their central business here. It is a busy place! But aside from the official business are all the people who live and work here in ordinary jobs, as well as all those who come here in the hopes of making a living of some kind. You will have your own impressions of what Mr Dickens is describing here! I myself am struck by the teeming humanity, the millions of people who crowd into London, at the same time as the dehumanised quality of the people and the city. Indeed, I felt that way when I arrived in the city!

We drove slowly through the dirtiest and darkest streets that ever were seen in the world (I thought) and in such a distracting state of confusion that I wondered how the people kept their senses, until we passed into sudden quietude under an old gateway and drove on through a silent square until we came to an odd nook in a corner, where there was an entrance up a steep, broad flight of stairs, like an entrance to a church. And there really was a churchyard outside under some cloisters, for I saw the gravestones from the staircase window. Bleak House, Chapter III, 'A Progress.'

Depiction of London in Bleak House.

Mr Dickens’s depiction of London in Bleak House is not always positive. He writes Bleak House out of a strong sense of social injustice. He emphasizes the teeming humanity, the chaos, poverty, and disorder, and he indicates that it is mainly the fault of those in power (in Parliament, in the Legal System, or ‘Chancery,’ as he terms it all). London is a city full of people, full of movement and life, but it is also a city of stasis, decay, and poverty. It is in desperate need of a more sanitary sewer and water system. Not every house has running water. Every household has a fire of some kind, and smoke rises into the air where it lingers. Sewers are not established across the city as a whole. Streets are full of muck from horses, animals, and households. Graveyards are overcrowded, and some individuals are not buried properly. Not every house has running water.

Mr Dickens sums up all this mess with the word ‘fog’, that polluting substance that covers the city—indeed, that covers us all. (Quote: Fog) He uses the term symbolically, to refer to the moral pollution and lack of care from the political and legal system and upper classes, as well as to refer literally to the physical unsanitary and polluted conditions of the city.

The raw afternoon is rawest, and the dense fog is densest, and the muddy streets are muddiest near that leaden-headed old obstruction, appropriate ornament for the threshold of a leaden-headed old corporation, Temple Bar. And hard by Temple Bar, in Lincoln's Inn Hall, at the very heart of the fog, sits the Lord High Chancellor in his High Court of Chancery. Never can there come fog too thick, never can there come mud and mire too deep, to assort with the groping and floundering condition which this High Court of Chancery, most pestilent of hoary sinners, holds this day in the sight of heaven and earth. Bleak House, Chapter I, 'In Chancery.'

I myself have experienced that fog. Indeed, when Mr Guppy, a young lawyer assisted me on my arrival in London I “asked him whether there was a great fire anywhere? For the streets were so full of dense brown smoke that scarcely anything was to be seen.” “Oh, dear no, miss,” he said. “This is a London particular.” I had never heard of such a thing. “A fog, miss,” said the young gentleman. “Oh, indeed!” said I. (BH, Chapter III: ‘A Progress’)

Indeed, fog is not always a strong enough word, as John Sutherland comments.

I would not quite put it that way myself! I am, however, aware of the truth of the statement. The fog is pestilential, laden with filth. It is as different from the fogs of the countryside as night from day. It is a fog created by the fires, and pipes, and sewers, and abattoirs, and kitchens, and steamboats, and horses and people that throng the city.

Filth, then, emerges as the true villain of Bleak house, surpassing the evils of the sadistic lawyer Tulkinghorn, or the homicidal Hortense, the insectoid stalker Guppy, or the vampiric Vholes. Specifically airborne filth, rising mephitically from the open sewers, from the 'nightsoil' (human excrememnt dumped in the gutters), and the animal droppings that caked the open streets. 'Mudfog' Dickens liked to call that poisonous atmosphere--for which read (and, with the mind's nose smell) 'shit-air.'

John Sutherland, Inside Bleak House: A Guide for the Modern Dickensian, London: Duckworth, 2005; p. 15.

Function of London in Bleak House.

In Bleak House, as with many of Mr Dickens’s novels, we oscillate between meticulously realistic representations and emotional, symbolic, and ideas-based representations. London is physically the key location in this novel, as I am sure you have noticed in the characters’ continual journeys to and from the city. As such, it functions as a metaphor for society as a whole, and for the country as a whole. Everyone in Britain knows of London, knows that it is the largest city, the capital, and the hub around which most activities circle to some degree. And in his depictions of London life, Mr Dickens is pointing to life in England as a whole, and life further afield still. London, then, is setting and symbol, a location for the action, and a place from which to think and reflect. When you read the novel, think about where people go when they go to London, where they live when they live in London, what they do on their visits, or in their daily activities. Think about the heart of London—where is it located, in real life, and in Bleak House. These are all ideas that Mr Dickens wants us to think about as we read!

To read Dickens is to encounter an urban writers whose work does not only rely on the city for the setting of plot and character, but rather situates London at the center of his fictions: it is the generator of plot and the determining element of scene and setting. Murray Baumgarten, 'Fictions of the City,' in John O. Jordan, Ed. The Cambridge Companion to Charles Dickens. Cambridge: 2005, 113-119; 113.

For instance, think about how Mr Dickens depicts the problems of London. Consider the opening of the novel, his somewhat sweeping and emotional references to fog as it covers the locations of the city. Mr Dickens becomes somewhat emotional when he is angry, as you may have noticed in his parts of the narrative of Bleak House, and he takes a somewhat sweeping view of things.

Dickens intended and hoped that Bleak House would not just describe or represent, but that it would be performatively efficacious, that it would be a way of doing something good with written words. J. Hillis Miller, 'Moments of Decision in Bleak House,' in John O. Jordan, Ed. The Cambridge Companion to Charles Dickens. Cambridge: 2001, 49-63, p. 59.

While fog is a real problem in the London of the time, Mr Dickens uses the idea of fog to refer to a range of problems in the city, most specifically to the problems of hygiene and sanitation. But as well as pointing to the social criticism of Bleak House, the opening to the novel is what you might call ‘cinematic’–it is, if not quite a bird’s-eye-view of the city, it is a view that covers the city, and ranges around the city as a whole. The symbolic, and literal, fog covers the city, the millions of people in it, hinting at, but also hiding, the huge scale of things.

It is my task, then, to clear away some of the fog, to show what lies beneath it, and to reveal important places, people, themes, and ideas in this novel. Come! We will proceed to the heart of the fog, to Chancery.